Consoles and Carcinization - How Gaming is Changing Forever

Either you die a Console or live long enough to become a PC

Hey There👋

Let’s kick off the new year right, with a piece on something that doesn’t get much attention but probably should.

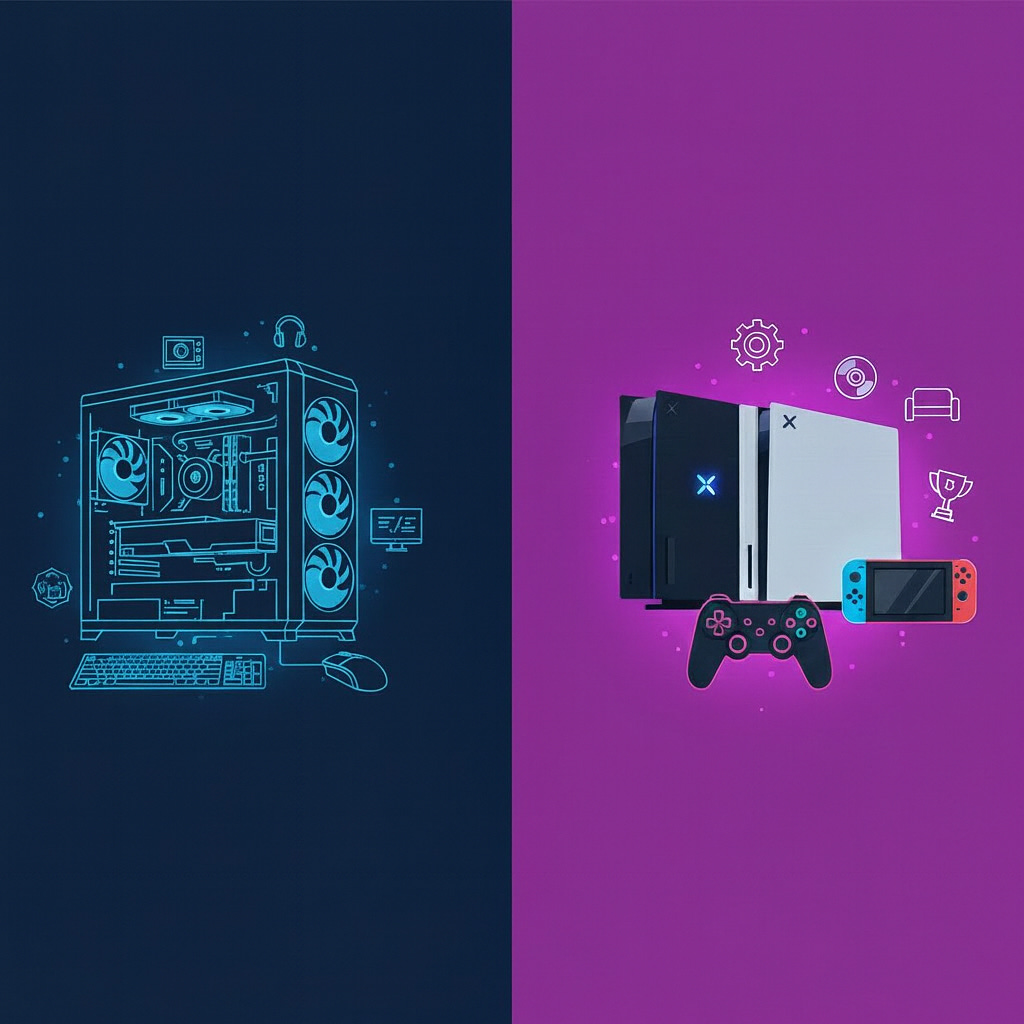

If you’ve been paying attention to gaming hardware lately, something weird is happening. The lines between consoles and PCs are getting blurry; and not by accident.

In the video games industry, we’re seeing a carcinization happen right before us as the two giants; PlayStation and Xbox turn more into actual PCs.

For a long, platform-exclusive games have been the selling point of gaming consoles. People used to buy consoles just to play games from franchises like The Last Of Us, Uncharted, God Of War.

In fact, more than the games, the hardware of these consoles has also started to become just like that of PCs. The newer consoles like the PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X use the same CPU and GPU architecture as PCs.

It feels that the consoles are fighting for their identity and Microsoft has only made it more obvious as they think of the next Xbox as a PC.

The general trend for AAA gaming appears to be moving towards PCs and as new entrants like Valve enter the market, we’re going to see some exciting shift going forward.

In the midst of this exciting trend, a devastating situation is emerging as the RAM pricing going as far as 400% in just a couple of months.

This exponential increase in RAM prices would have a far-reaching impact on both PCs and consoles going forward, and I’ll touch a little bit on that too in this article.

Here’s an overview of what this article would talk about:

Some history of the earlier consoles and what made them special

Why consoles are converging to PCs

What’s the strategy for the three big players (Sony, Xbox, Nintendo)

How Valve’s entry may shake things up

What the future looks like

When Consoles Were Truly Different

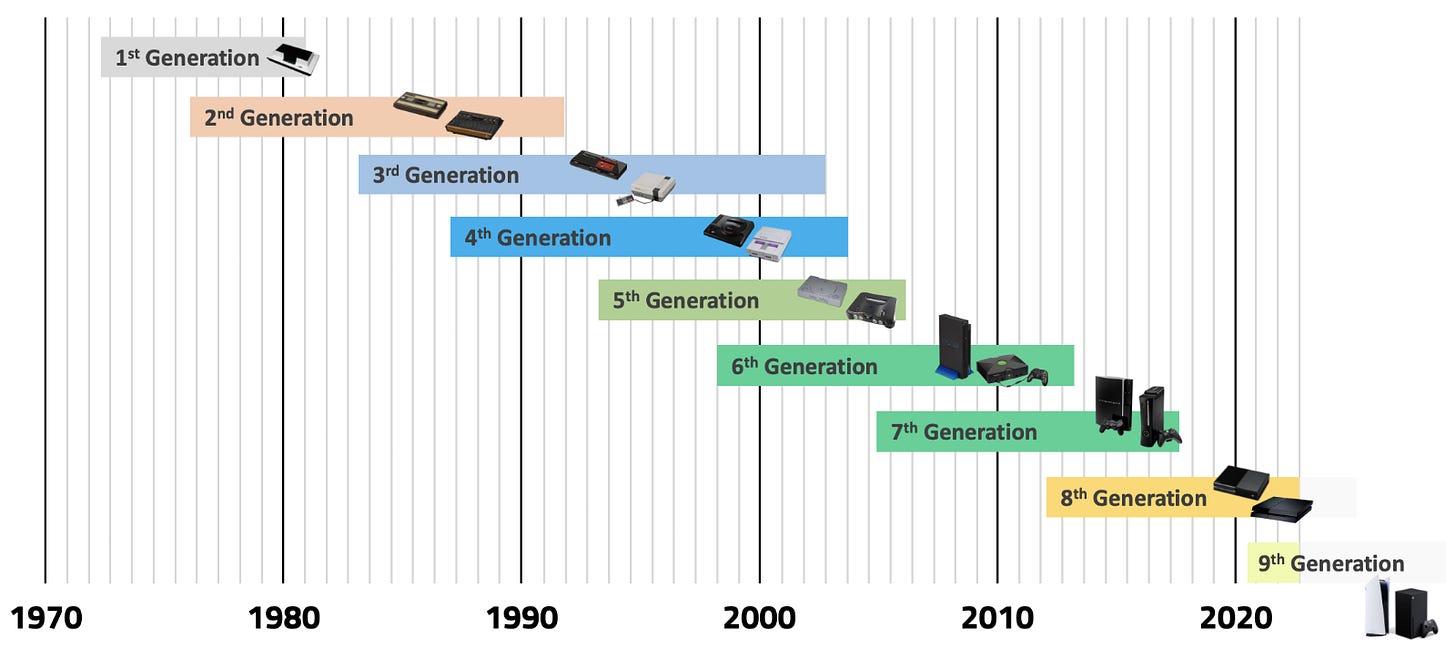

Video Game Consoles are generally divided into generations. This isn’t a definitive list but most people generally agree on it.

The First generation of consoles starts with the likes of Atari 2600, released back in the 1970s. As of 2025, we are on the Ninth generation of consoles.

Covering all of the generations isn’t the point of this article. That’s why we’ll start our discussion with the Sixth generation of consoles that roughly starts from the year 1998.

Note: For each of the console generations, I’m taking the release year as the starting point and the launch of the next generation as the ending point for the previous one.

Sixth Generation of Consoles (1998-2004)

The sixth generation of consoles is when the PlayStation 2, the original Xbox, Sega Dreamcast and Nintendo GameCube released. All of them were released around late 1990s to early 2000s.

To date, PlayStation 2 is the most sold gaming console with over 160 million units sold. The Xbox was a huge success too selling over 24 million units and this generation is the one that got us classics like HALO, God Of War.

Seventh Generation of Consoles (2005-2011)

This is believed by many to be the best generation. That is because we had some of the best competition from both sides (Sony and Microsoft) that delivered unforgettable experiences.

The seventh generation got us consoles like the PlayStation 3, Xbox 360 and the gaming catalogue that includes Demon’s Souls, The Last of Us, Gears of War 2, Halo 3, and many more.

Eighth Generation of Consoles (2012-2019)

The eighth generation began in 2012, and is made up of four home video game consoles:

Wii U

PlayStation 4

Xbox One family

Nintendo Switch

On the AAA front, PlayStation 4 was a huge success with classics like Bloodborne, God Of War (2018), Marvel’s Spiderman. The Xbox One was sadly the console that started Xbox’s decline that continues to date.

Console vs PC hardware

Up till the seventh generation, most of the gaming consoles were custom-built devices that had everything from their processor and graphics chips that were specialized.

All the way from early Sega consoles to PS3, most of these consoles had custom processors. The PlayStation 3’s main processor (Cell Broadband Engine) was notorious for being hard to develop games for.

The original Xbox, although used x86, switched to a custom processor architecture (PowerPC) for the Xbox 360 which shifted again to x86 for the Xbox One, that released in 2013 (talk of U-turns :p).

On the PC side, things were pretty simple. Historically, they’ve been only two processor manufacturers, implementing the same x86 processor architecture.

To this day, it holds up. The x86 processor architecture still reigns supreme in the PC space, but tides are turning.

I’m discussing these technical details just to build up the context for the next section.

The point is that gaming consoles historically have been custom devices that were built differently from computers. Their processors, their graphics chips, were very different from PCs.

To sum it up: Consoles weren’t PCs - they were purpose-built machines with unique hardware identities.

Consoles Becoming PCs

The Hardware Side

We just talked about the history of consoles and how they have largely been different from PCs. While that was true for a long time it isn’t the case these days.

Modern consoles, especially the two big ones; Xbox and PlayStation, have shifted this approach and now they’re almost a PC from a hardware perspective.

Starting with the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One (2013), the hardware has started to look a lot more like that of PCs.

It turns out that both Sony and Microsoft have contracted with AMD to produce their PlayStation 4 and Xbox One hardware.

Both companies are using the same processor design (Zen) and more importantly they use the same Instruction-Set Architecture that is used by PCs (x86).

If you don’t know what Instruction-Set Architecture is, I’ve written a clean blog explaining it in a simple way. You can check it out below:

Using x86 means that the games that developers write for the consoles are relatively easy to port over to PCs because the underlying architecture is the same as PCs.

And that’s part of the reason why we’re seeing Sony exclusive titles make their way to the PC.

Before the PS4 and Xbox One generation, consoles from both sides used custom processors that had completely different processor architecture to PCs.

Not only were they difficult to develop with but also it was a nightmare to port those games over to the consoles. That is part of the reason we still have classics like God Of War 3, still not available on PC to date.

The point is that today’s consoles like the PlayStation 5 and the Xbox Series S/S are fundamentally the same as a PC from a hardware perspective. They use the same CPU architecture that PCs use, they use the same GPU architecture that the PCs use.

But that’s not at all to say that all consoles are now similar to PCs, we still have a big player like Nintendo whose consoles aren’t that similar to a PC.

While the two big console manufacturers have shifted to PC hardware, that isn’t to say that everyone has done that.

In fact Nintendo is a great example of a console manufacturer that uses the ARM architecture for its consoles. Its approach still looks like that of the previous consoles where much of the console is pretty different from a PC.

The Software Story

It looks like the hardware for both PCs and modern consoles is converging. While that’s true, the software side is also in a weird spot.

Back with the earlier consoles, games were primarily developed for specific consoles oftentimes by the game studios owned by console manufacturers. Take Naughty Dog for example, who created the Uncharted and The Last of Us franchise.

The game studios were provided with devkits for the consoles and they had access to the exact specifications of the consoles that they were developing games for.

But these days, a large community of developers (especially indie ones) focus on developing first for the PC and then porting it over to consoles. Previously, the exact opposite used to happen.

Still, many large studios prioritize developing on consoles because that gives them access to a stable hardware platform that they’ve been accustomed to.

Xbox: The Console that Became a PC

The Console That Once Was

Xbox started out as an answer to PlayStation, and Microsoft gave Sony a great run for its money with its two successful consoles; the original Xbox and Xbox 360.

Xbox 360 was Microsoft’s last hit and the console on the hardware side was a true console with custom processor architecture, good exclusives and overall a great package at a good price.

That’s the reason the Xbox 360 sold over 85 million units!

But starting with Xbox One (2013), things began to take a totally different turn, and that too for the worse.

When the two consoles (PS4 and Xbox One) were against each other back in 2013, Xbox One just didn’t have a chance and since then Microsoft has taken a different approach to Xbox as a platform.

Microsoft no longer sees Xbox as a console but rather an extension of Windows. Their Game Pass subscription looks more like the product than the console.

The recent price hikes to Game Pass have also weakened the argument for it which was a strong point for the Xbox platform for quite some time.

Modern Xbox uses PC hardware - It has the same processor architecture and design as a regular PC processor, the story is the same for the GPU and storage.

On the software side too, Xbox uses the Windows kernel and cross-store apps. And the Xbox app on PC also supports many of the Xbox games already taking more of the exclusivity away from the console.

More than anything else, the modern Xbox has a perception problem. It is simply seen as a Windows PC that is somehow limited.

If you strip an Xbox Series console down to its fundamentals, what you’re left with is basically a Windows PC in a console-shaped shell. Microsoft stopped pretending otherwise a while ago.

The current Xbox uses the same x86 architecture. A Windows-like OS. Similar development tools. And increasingly, the same software library.

Game Pass Subscription

With Game Pass, Microsoft made it clear that the real product isn’t the Xbox box sitting under your TV.

It’s the subscription. New first-party games now launch day one on both Xbox and PC, and sometimes don’t even bother pretending that one platform is more important than the other.

On paper, this sounds great. One ecosystem. One library. Play anywhere.

In practice, it created an identity problem. To a lot of players, Xbox now feels like a small Windows PC that you’re not allowed to fully control.

You’re locked into Microsoft’s store, locked into its UI decisions, and locked into its update system.

And that store has a reputation problem of its own. Bugs, broken downloads, UI issues, and random errors are common complaints on both PC and console.

That frustration got worse when Game Pass prices went back up just recently. Back in October, Microsoft issued a 50% price increase to Game Pass out of nowhere.

When you’re paying more every month, you start asking harder questions about what you’re actually getting. And for many players, the answer felt like “a PC, but worse.”

Microsoft’s strategy of putting its first-party games everywhere only accelerated this feeling. When Xbox exclusives show up on PlayStation, Switch, and PC, the console loses the one thing that historically justified its existence.

Xbox is already a PC. It just doesn’t offer the openness people expect from one.

Sony: Slowly Becoming a PC Company Too

Sony’s shift has been quieter, but just as important.

At first, PlayStation games coming to PC felt like a bonus. Older titles like Horizon Zero Dawn and God of War showed up years later, long after their console runs had peaked. It felt harmless, even smart.

Then the gap started shrinking.

By 2024 and 2025, Sony became much more comfortable talking about PCs as a core revenue stream. Big PlayStation titles were no longer “never coming to PC,” just “not yet.” In some cases, that “yet” wasn’t very long.

And that creates an uncomfortable question for PlayStation too.

If the hardware is increasingly PC-like, and the games eventually come to PC anyway, what exactly is the PlayStation box selling you? Convenience? Branding? Timed exclusivity?

Sony still has more cultural gravity than Xbox. PlayStation is tied to decades of iconic franchises and moments. But that also means Sony has more to lose.

Xbox already embraced being a service-first platform. PlayStation’s identity is still built on the idea of a special box that plays special games. That identity is now under pressure.

Sony isn’t fully there yet, but the direction is clear. The more PlayStation leans into PC revenue, the harder it becomes to justify a closed console ecosystem.

Sony isn’t fully “crabified” yet like Xbox, but the evolution is happening. PlayStation’s identity is at stake more than Xbox’s.

Nintendo: The Last Traditional Console Maker

Nintendo lives in a completely different universe.

While Sony and Microsoft chased performance and parity, Nintendo opted out of the race entirely. Its hardware has never been about specs.

It’s about form factor, interaction, and first-party games that are designed specifically for that hardware.

The Switch didn’t succeed because it was powerful. It succeeded because it was different.

Nintendo’s biggest franchises don’t just run on its hardware. They are shaped by it. Mario, Zelda, and Pokémon exist inside a tightly controlled ecosystem that doesn’t need PC parity to thrive.

You buy Nintendo hardware because you want Nintendo games, not because it competes with your PC.

That’s why Nintendo feels oddly immune to this whole “consoles becoming PCs” trend. It’s not trying to be a PC. It’s not chasing raw performance. And it doesn’t rely on third-party parity to justify its existence.

If current trends continue, Nintendo might be the only major console maker left with a truly distinct identity by the end of this decade.

Valve’s Return to the Living Room: The GabeCube?

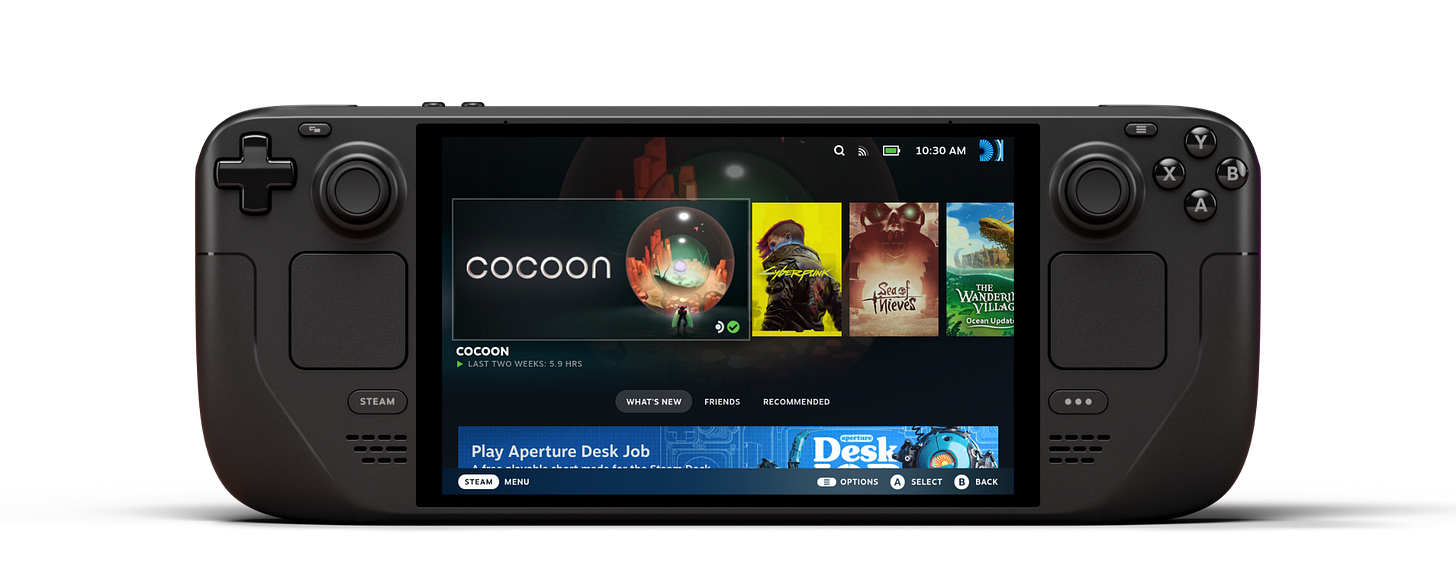

Valve already tried to turn the PC into a console once, and it failed hard.

Steam Machines, first announced in 2013 and quietly abandoned a few years later, were supposed to bring PC gaming into the living room. The idea was cool, but the execution wasn’t.

Linux gaming support was weak, driver support was inconsistent, and the experience varied wildly depending on the manufacturer.

Most importantly, there was no compelling reason for regular players to choose a Steam Machine over a PlayStation or Xbox. There just weren’t that many games to play.

Fast forward to the mid-2020s, and almost every problem that killed the initial Steam Machines no longer exists.

SteamDeck’s Success & Valve’s Edge

The Steam Deck wasn’t just a successful product. It was proof that Valve finally solved the hardest problem in PC gaming: making it feel console-like without killing what makes PC gaming powerful.

Proton now runs the vast majority of Windows games with minimal effort from the user. SteamOS 3 is stable, fast, and purpose-built for gaming. And Valve controls the full stack in a way it never did before.

This matters because Valve doesn’t need exclusives to compete.

There’s a more detailed answer to Why SteamDeck Won, you may checkout my recent article on the topic to learn more:

A living-room SteamOS console today would launch with access to tens of thousands of games on day one. Not future promises. Not “coming soon.” Actual libraries people already own.

That alone gives Valve a structural advantage that Sony and Microsoft simply don’t have. More importantly, Valve understands something the console makers seem to be forgetting: trust.

Steam has spent two decades building goodwill with PC players. Refunds are simple. Mods are supported. Community features are first-class citizens.

The platform doesn’t fight its users at every step. When Valve ships hardware, people are willing to give it the benefit of the doubt because the software ecosystem already works.

The Steam Deck succeeded not because it was powerful, but because it respected the player. It didn’t lock you out of other stores. It didn’t pretend to be something it wasn’t. It was honest about being a PC, just one designed to be approachable.

Steam Machine 2.0

The recently announced Steam Machine could take that same philosophy and scale it up. Standardized hardware. Controller-first UI. Seamless suspend and resume. Couch-friendly ergonomics.

This time, Valve isn’t asking people to gamble on Linux gaming. It isn’t asking devs to write games for Linux. Proton compatibility layer is now mainstream, documented, and battle-tested.

If you’re wondering what Proton compatibility layer is about. I covered it in detail in my SteamDeck article that I shared in the previous section.

Even major publishers like EA and Ubisoft have had to quietly accept that their games run well on Linux via Proton, whether they like it or not.

If Valve prices the Steam Machine aggressively, the impact could be massive.

What does the Steam Machine mean for Sony & Microsoft?

For Sony, it would accelerate the pressure to justify PlayStation hardware at all. Why buy a closed box when a Steam console gives you your entire PC library and future access to everything else? For Microsoft, it could be existential.

Xbox already struggles with identity. A successful Steam console would complete Xbox’s transformation into “a PC ecosystem without hardware relevance.”

Valve doesn’t need to win the console war outright. It only needs to destabilize it.

And unlike Sony or Microsoft, Valve doesn’t need hardware margins to survive. Steam prints money. Hardware is leverage, not a lifeline.

That’s what makes Valve the most dangerous player in this entire convergence story.

It doesn’t need to rush. It doesn’t need to overpromise. It can wait until the moment is right and quietly ship something that reframes the entire market.

That’s why Valve is the biggest dark horse in the console/PC convergence race.

The Storefront War: Steam vs The Rest

By 2026, the most important battlefield in gaming is no longer silicon, teraflops, or console form factors. It’s storefronts.

Hardware has become increasingly commoditized. CPUs and GPUs across platforms are closer in capability than ever. Even consoles now resemble tightly controlled PCs, sharing similar architectures and development pipelines.

What actually differentiates ecosystems today is not the box under the TV, but where your games live, how easily you can access them, and how much trust you place in the platform holding your purchases.

This is where the gap between Steam, Microsoft, and Sony becomes glaring.

State of Microsoft Store

The Microsoft Store is widely regarded as one of the weakest major digital storefronts in gaming. This reputation didn’t form overnight.

Years of buggy downloads, stalled updates, broken installs, confusing UI changes, and poor error reporting have eroded user confidence.

These problems exist both on Windows and across the Xbox ecosystem, where the Store is unavoidable.

What makes this worse is that Microsoft forces interaction with the Store. Even users who would otherwise avoid it are pushed into it through Game Pass, system updates, and platform-level integrations.

For a time, Game Pass softened the blow. The value proposition was strong enough that users tolerated the experience but that value is gone too after price hikes leaving gamers furious.

When the price goes up, flaws stop being “quirks” and start being deal-breakers.

Sony’s PC Strategy

Sony now appears to be considering its own PC storefront, and this is where things get especially risky.

On paper, the move makes sense. Sony wants more control over revenue, data, and customer relationships.

Sony selling its games through Steam means giving Valve a cut and surrendering platform-level influence. But launching a new storefront in 2025 isn’t like launching one in 2005.

Why is Steam So Hard to Replace?

Steam already exists, and more importantly, it already works better than the others. Steam isn’t dominant because it’s the only option. It’s dominant because it consistently does the basics right.

On Steam:

Downloads are reliable

Refunds are straightforward

Cloud saves are mostly invisible in the best way possible

Mod support is deeply integrated

Community features aren’t an afterthought

Over time, Steam has accumulated not just libraries, but goodwill. That goodwill is incredibly hard to replicate.

Sony’s reputation on PC is already mixed. Account requirements, regional lockouts, and inconsistent support have caused backlash even when Sony releases games on Steam, a platform people trust.

Moving those same users to a proprietary Sony storefront would mean asking them to give up features they already like in exchange for… what, exactly?

Exclusives alone are no longer enough. Players have learned that “exclusive” often just means “delayed.”

Once users expect a game to arrive elsewhere eventually, the leverage of exclusivity weakens. Without a superior platform experience, a new storefront becomes friction instead of value.

Steam, by contrast, has become the gold standard almost by accident.

Valve rarely markets Steam aggressively. It doesn’t need to. Steam’s power comes from being boring in the best possible way.

It’s predictable. It doesn’t fight users. It doesn’t constantly redesign itself to chase trends. It quietly improves infrastructure while letting players focus on games.

If you’re tempted to learn how Valve wins without ‘doing’ anything, here’s another recent article we did going to lengths into the company’s origins and major breakthroughs:

That’s why storefront dominance matters more than hardware in 2025.

A storefront isn’t just where you buy games. It’s where recurring revenue lives. DLC, expansions, cosmetic purchases, subscriptions, cloud saves, and social features all flow through it.

Hardware is sold once. Ecosystems extract value continuously. This is why every major company wants to own the store, not just the console.

Storefronts also enable ecosystem lock-in in ways hardware no longer can. Your friends list, achievements, mods, screenshots, play history, and library size all create inertia.

Switching platforms doesn’t just mean buying new hardware; it means abandoning years of digital identity. Steam understands this better than anyone, which is why it invests heavily in features that make leaving feel costly, but staying feel comfortable.

Cloud gaming and cross-device support further amplify this effect. A strong storefront follows you across desktop, handheld, living room, and eventually the cloud.

Steam already spans most of these contexts. Microsoft is trying to do the same, but its storefront experience undermines its ambition. Sony is entering late, without the trust buffer Valve has built over decades.

This is why Valve entering the living room with serious hardware should not be underestimated.

Valve’s Ecosystem Strategy

If Valve ships a standardized SteamOS console and their new VR headset, it doesn’t need to convince users to adopt a new ecosystem. The ecosystem is already there.

The hardware simply becomes another access point. Suddenly, the strongest storefront in gaming history is no longer confined to desks and keyboards.

It’s on the couch, under the TV, paired with a controller or strapped to your head with controllers in your hands.

At that point, Sony and Microsoft aren’t competing with consoles anymore. They’re competing with an ecosystem that already owns player loyalty.

And unlike its competitors, Valve doesn’t need to force adoption. It doesn’t need exclusives. It doesn’t need subscriptions to be mandatory. It only needs to make access easier.

In a world where consoles are increasingly PC-like, the best ecosystem wins.

What Consoles Become After 2025

By the time we pass 2025, the shape of the modern console is no longer confusing. The industry has converged, and the “crab” form is unmistakable.

Modern consoles now share the same x86-64 architecture as PCs

They run operating systems derived from desktop-class kernels

They rely on the same engines, the same graphics APIs, the same middleware, and increasingly the same binaries

Ports are no longer special events; they are the default

Development pipelines assume multi-platform releases from day one

This convergence wasn’t accidental. It was the logical outcome of rising development costs, lengthy production timelines, and the economic pressure of maintaining custom platforms.

Writing custom hardware architectures and bespoke software stacks became a liability rather than a competitive advantage. As a result, consoles stopped winning by being fundamentally different.

In earlier generations, hardware identity mattered deeply. The PlayStation 2, Xbox 360, and even the PlayStation 4 era were defined by architectural quirks, proprietary APIs, and tightly controlled ecosystems.

Owning a console meant buying into a unique technical environment. Developers optimized for it. Players accepted its limitations because there were no alternatives. That era is over.

Why Flashy Specs Don’t Matter?

In the post-2025 landscape, consoles are best understood as curated PCs with fixed specifications. They exist to simplify access to gaming. Their value lies in predictability, ease of use, and smooth ecosystems rather than raw technical specifications.

This is why hardware specs have lost their narrative power. Teraflops no longer move audiences. SSD speeds no longer dominate headlines. Performance parity across platforms has flattened expectations.

When everything runs well enough, “more power” stops being a selling point. Instead, access becomes the metric that matters.

Consoles are no longer sold as machines; they are sold as gateways. Gateways to libraries, subscriptions, social graphs, cloud services, and cross-device play. The box itself is secondary.

What matters is how frictionless it is to reach games. This is where ecosystem battles replace hardware battles.

An ecosystem decides whether your purchases follow you across generations. Whether your saves sync automatically. Whether your friends list persists. Whether your library expands or fragments over time.

The more invisible these systems become, the more valuable they are.

Microsoft understands this, which is why Xbox hardware increasingly feels like a delivery mechanism for Game Pass rather than a product with its own identity.

Sony is moving in the same direction more cautiously, expanding PlayStation into a broader services platform rather than a single-device experience.

Valve approaches the problem from the opposite end, letting the ecosystem exist independently of hardware.

In all cases, the console’s role is shrinking relative to the catalog it unlocks.

This shift explains why exclusivity has weakened as a strategy. Exclusives once justified hardware ownership. Today, they mostly justify temporary hardware ownership.

When users expect games to arrive elsewhere eventually, the urgency to commit to a single box disappears. Consoles must therefore compete on convenience rather than scarcity.

And convenience is not about power. It’s about continuity.

What Matters, Then?

A successful post-2025 console minimizes decision-making. It remembers your preferences. It works across devices. It respects your time.

It doesn’t fight you over updates, storage, or licensing. It makes accessing your catalog feel inevitable rather than conditional.

Consoles sit alongside handhelds, PCs, cloud clients, and mobile devices as one of many ways to reach the same ecosystem. This is why multi-device strategies are no longer optional.

A console that only works in the living room is incomplete by modern standards. Cross-progression, cross-buy, and cross-save are not “features” anymore. They are expectations.

Consoles promise stability. They promise compatibility. They promise access without friction. In doing so, they quietly acknowledge that differentiation through hardware alone is no longer viable.

This also explains why nostalgia-driven arguments about consoles “losing their soul” feel both accurate and incomplete.

Yes, consoles have lost some of their mystique. They are no longer strange, bespoke machines with exotic architectures. But that loss of mystery is the price of scale.

You cannot build global, cross-device ecosystems on fragile, hyper-specialized hardware. The future console is boring by design.

It exists to disappear behind the software layer, leaving only the experience of the catalog itself. In that world, the best console is not the most powerful or the most unique. It is the one that feels least obstructive.

This is the final stage of convergence.

After 2025, consoles do not win by being different from PCs. They win by being the best way to not think about PCs at all.

What I’m Excited For

For me, the console and gaming industry as a whole is in a transition period. A period where we not only have standardized hardware across the big players but also one where we’re seeing some real shifts happening.

The current generation of consoles isn’t exciting for me. We just don’t have as impressive of a first-party games catalogue like we had with the previous generations.

Both PS5 and Xbox have serious improvements from a game performance POV but there just haven’t been that many games to be excited about, at least for me.

A lot of what has me excited for the future of gaming comes from Valve. Their recent announcement on their upcoming hardware like the Steam Frame, Steam Machine and their controller is what I’m really looking forward to.

Valve doesn’t call their Steam Machine a console but it’d directly compete with the likes of Xbox.

For me, I’m excited about the underlying software technology that Valve is bringing with their hardware.

Their open approach to figuring out game compatibility across operating systems and hardware through layers like Proton, Fex is really exciting for me.

And for some reason I personally believe that Valve just wouldn’t pass the moment of releasing Half-Life 3 with the Steam Machine. I mean, could there ever be a better time?

What I’m Scared Of

I’m generally excited for not just new hardware that’s coming up this year especially from Valve which includes the Steam Frame, Steam Machine and the controller.

But the ongoing price increase of RAM does make me concerned about the future of gaming atleast in the short-term while the AI bubble continues to make consumer hardware out-of-reach for many.

In the last couple of months we’ve seen RAM get 4x the price of what is used to be just few months ago.

A 64 GB kit of DDR5 RAM now costs more than a Playstation 5!

And as I write this, RAM prices continue to increase. I went to a Gaming PC shop a month or so ago and they were quoting RAM prices on weekly basis.

What this means is that going forward new launches of consumer hardware be it consoles, PCs, even laptops and smartphones would be expected to cost more simply because of more expensive RAM.

It is also possible that if the situation continues to go out-of-hand, companies may delay hardware releases for the time being.

To discuss this RAM crises in detail, I’m working on a detailed article that answers why is RAM suddenly expensive, how far can it go, and who would be affected. So, stay tuned for that!

As always Thank You (yes you the reader!) for going through this rather long deep-dive. I had fun writing this as much as researching it and I hope you enjoyed the read.

You know I love engaging with my audience. Your comments, engagement directly improve my work, and help SK NEXUS grow as a community and as a publication.

So please leave any of your questions, opinions or criticisms down below. I’d love to discuss how you feel about consoles, PC, gaming and the upcoming developments in the scene.

I reply to each of the comments so there’s no reason to hold back.

You’re also welcome to share this piece with a fellow gamer through the button below: